Trigger warning: candid discussions of witnesses, of death, of suicide, including mention of method—gun.

The first time I put ‘the man and his dog’ into a work of art, they were peripheral, nearly invisible. In the story of my mom’s suicide, they were set dressing, just another fact in a sea of facts—”saw a man walking his dog / 911”.

It wasn’t until three years and a pivotal book later that I began to consider them as key characters to the story, began to wonder and worry, began to write to and speak to them from a place they’d never reach. In January of 2023, I read (well, listened to the audiobook while driving across state lines) All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell. Within moments I felt that Campbell was speaking directly to me, reaching into my chest and rattling my rib cage, depositing wisdom directly inside of me. Or something like that. The book is a death curious journalist, Campbell, embarking on a journey of discovering what happens to us after we die–what really happens to us. From the folks to collect the body where they died, to the morticians washing and embalming and caring for them, to the crematory workers and the grave-diggers and the cadavers at the Mayo Clinics to executioners and those interested in cryogenic freezing and stillbirth doulas. It was a profound and glorious peek into the massive world of death, yes, but more specifically the profound level of empathy and care that death care workers offer the dead. I had to pull over and cry before the introduction was even over, and when I was done reading it, I sat down and tearfully wrote thank you letters to the people who’d cared for my mother most immediately after her death. I never sent them, and they’re on a hard drive somewhere in storage now, but it was a gift to me to be nudged toward acknowledging the everyday people that played such an important part in her life and death.

One of these people was a man walking his dog.

It was a Thursday a few minutes past 3:20 pm when my mom, Treva, took her life (as I wrote in a 2020 poem, “I don’t even know if it was exactly 3:21 pm. / It could have been 3:22, 3:23, 3:24…. / but 3:21 pm hits like a corkscrew pulling up on my heart. / So I think it was then.”1) and it was something like five minutes later when my dad tore through the bramble and the roots and the branches, following the pinging GPS dot that was all that was left of my mom, and so it was some time like 3:27 pm on a crisp January day in local park–one with trails and trees and lakes and trees and boulders–when a man was walking his dog along the path past a woman between a rock and a hard place and a man holding her tightly in his arms (warm, she was still warm). It was some time like 3:27 pm when this man with his dog was flagged down by a stranger, a terrified stranger shouting for help, for a hand, for a body–would he go stand in the parking lot? Would he wait for the police? His wife had just killed herself and he couldn’t leave her alone there, would he wait for him? And he did.

This is all I know. All I know is a man, all I know is a dog, all I know is a cry, all I know is a request, all I know is turning on a heel and four paws and standing, sentinel, at the parking lot.

I realized recently that when I picture this scene, I imagined the man and his dog were at the end of their walk, looping back around the trail toward the parking lot after a pleasant jaunt, but I realize even this I don’t know. Had they just stepped into the park (the man and his wife by the boulder were not far from the entrance to the park), or were they just leaving? Was the man old or young or white or Black or or or? Was the dog big or small, wiry or soft, could they sense something was wrong? Did the man run or walk to the parking lot? Was he hesitant? Was he okay? Is he okay? Does he still think of it? Was the dog afraid? Was he afraid? Did he call someone while he waited? Did his heart hammer? Did he shake? Was he affected? Was he affected?

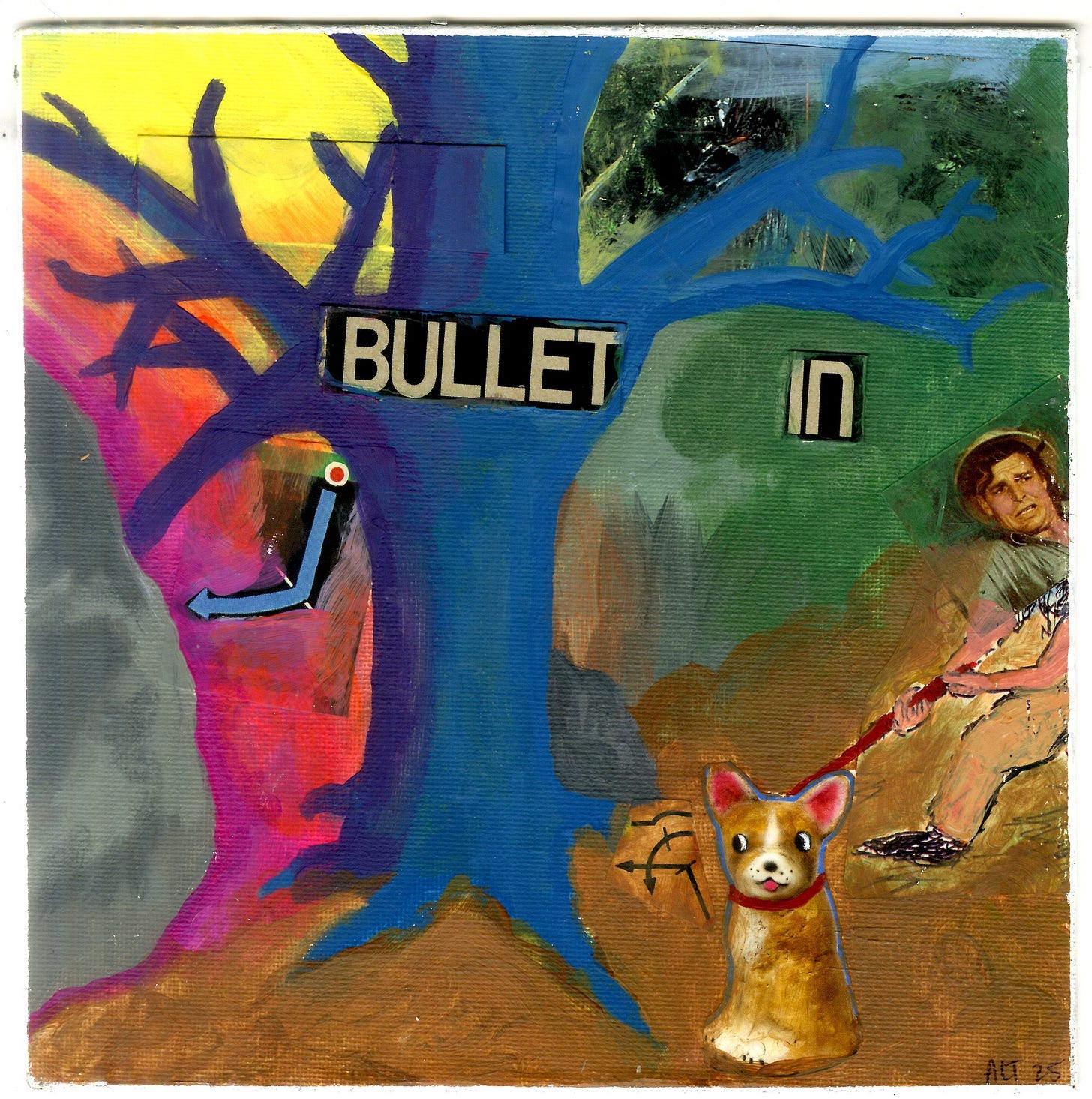

In the last year I have found myself reaching out to him, “even if each word I put down is one word further from where [he is].”2 I’ve found myself trying to make sense of this speculative memory, using collage to try to piece together a man I don’t know and can’t know meditating almost obsessively on the above questions (how many times can I say the same thing and still not know what it means?).

Were they coming or going?

Did he move slowly or quickly?

How much did the dog know?

How much did he see?

How much did he hear?

Was he afraid?

Does he still think of it?

What color is this memory for him? What shape?

Is he okay?

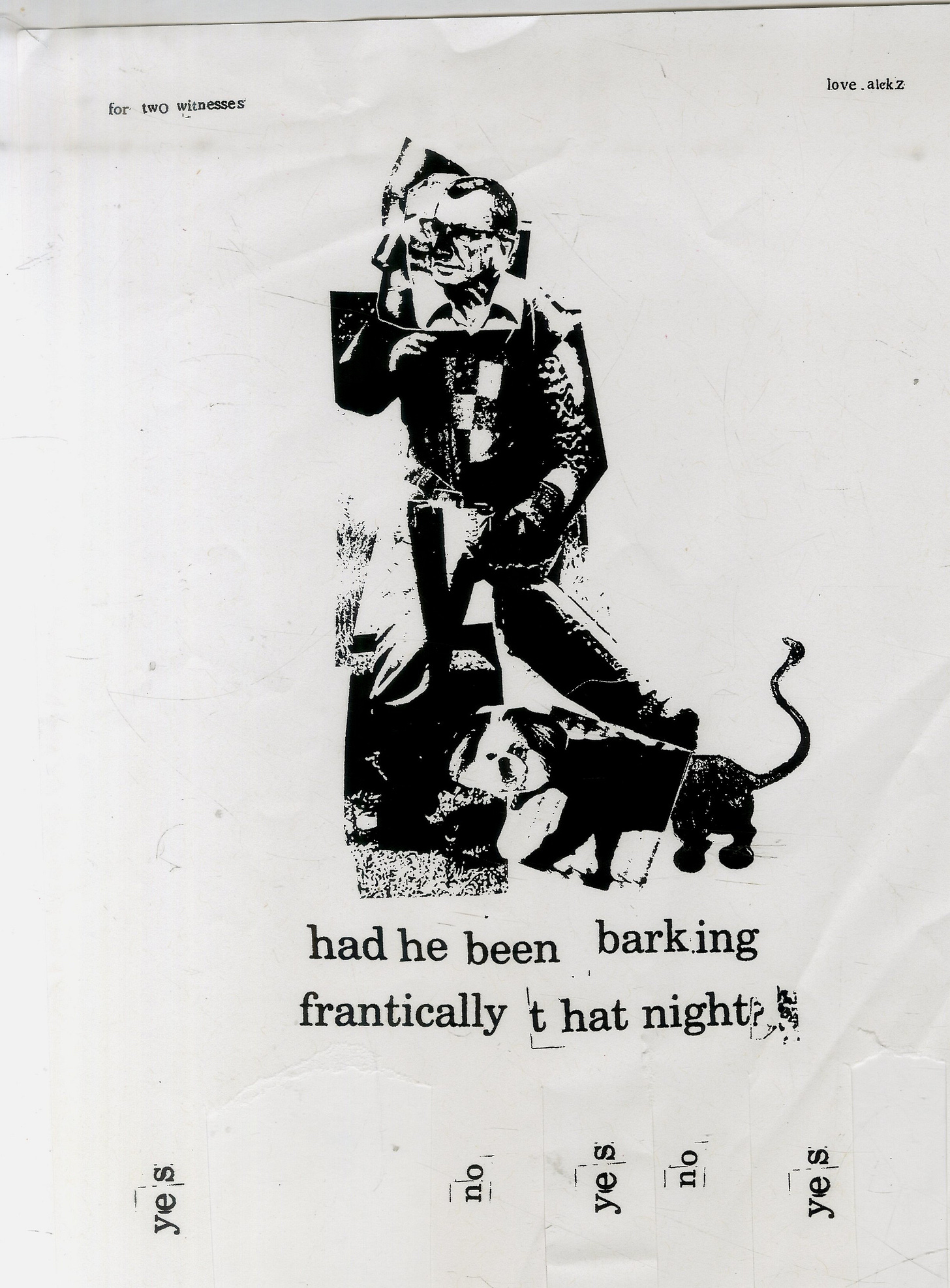

I collaged questions “for the 2 witnesses” together, made flyers and posters, a few of which made it to subway and scaffold walls (only the smallest ones that I could put up with one hand, which is to say the pipsqueakiest ones that make the most pathetic visual impact) (the rest are still in the corner of my studio because I am allergic to logistics and could never iron out a performance, loathe as I always am to burden someone else with my whims yet unable as I am to do it alone. Another idea of this type is in the works, however…time will tell us how that goes).

People say it’s funny how I focus so much on such a minor character. But when I really think about it, he is huge. It’s one of the very few moments of mystery in the whole saga of her suicide. I am such a caretaker that I feel almost bereft that I can’t check in on this person, however minor someone perceives him to be. He was there. He was that at the moment every everything change. When my world lost its color and the land once more became a mother cradling her child as she slept. Seven billion people in the world and there were only two beating hearts in that clearing. That matters. Those odds matter. This man and his dog matter.

This body of work is a reaching out to, a reaching towards, a beseeching, an imagining, a postcard, and thank you note, a missing poster, a fabulation.

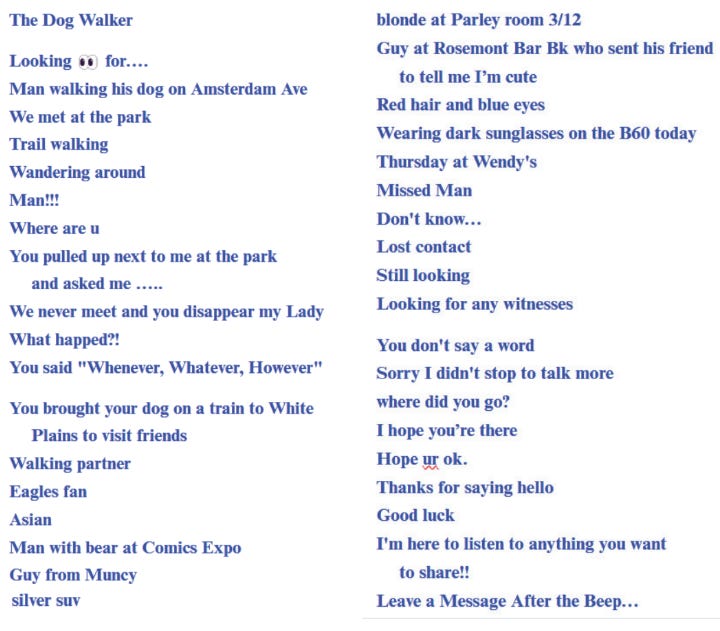

It’s a missed connection.

I recently dove into the world of craigslist missed connections, a corner of the internet I’d only poked around in in the past, I spent hours over days cataloguing missed connections, in awe of the human desire to build connection, the tender way people would start an entry by addressing the readership at large before subconsciously slipping into talking directly to the missed connection. The hope you have to have to put out a call and believe you’ll get a response because a missed connection requires hope–they are mutually inclusive, they are a set: must not separate. There is humanity. There are sometimes creepy dudes (which is, again, humanity in the fullness of her being, duality of man and all that), but there is hope. And there are people posting just to say thank you to someone for holding a door, or replacing a windshield wiper, or saying a kind word. There are people looking for long lost friends, schoolmates from decades past, phone numbers lost–I could go on and on about how kinetic and thrumming with life the missed connections site is, but for our purposes here I’ll turn back toward the man and his dog. It wasn’t even until days of working with the missed connections that I realized that what “The Witnesses” is is one big missed connection post talking past the readership at large straight to the missed connection.3 And I don’t expect to ever know who the man is, but I do hope that someone who my work invites to remember feels…seen? I hope that maybe someone who needs a chance to remember is given space to remember, whatever that means.

Everyone has their own Man & Dog. No one dies truly alone. Maybe someone’s Man & Dog is the hospice nurse, maybe it’s the runner, maybe it’s the spouse, or the mother, maybe it’s the bird flying by or the tree that asks the wind to bend it to provide shade, maybe it’s the wind caressing them for the last time. Someone is always there, even if they didn’t ask to be. I’ve been the witness in a high rise hearing someone be attacked, not knowing where exactly in the expanse of windows above and below and beside my own the hurt was happening. I’ve been a witness calling for help and being told the building is too big and they’re suddenly quiet so there’s nothing that could do. I often wish there was a way I could tell that girl that I tried to help. I hope she knows her cries were heard, and she wasn’t ignored and she wasn’t invisible and that it wasn’t her fault. I tried. I tried to be her Man & Dog, but maybe we’re not all on the right side of the trail head when the clock strikes 3:27. I don’t know.

Love,

Alekz

You died around the same time I was born, 2/24/20, from in permanent january by Alekz Thoms.

“I don’t know exactly when I was born either. / 3:30 pm is the approximation you gave me./ That feels too round, but I know my time and your time/ hook arms like dancers in a circle./ jagged on soft,/ holding each other in the tension of difference./ Birth and death./ You died around the same time I was born,/ holding each other in the tension of difference.”

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong